Parentã¢â‚¬â€œchild Interactions and Obesity Prevention a Systematic Review of the Literature

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

Family-based childhood obesity prevention interventions: a systematic review and quantitative content analysis

International Periodical of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity volume fourteen, Article number:113 (2017) Cite this commodity

Abstruse

Background

A wide range of interventions has been implemented and tested to preclude obesity in children. Given parents' influence and control over children's energy-rest behaviors, including diet, physical activity, media employ, and sleep, family interventions are a fundamental strategy in this effort. The objective of this study was to contour the field of recent family unit-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions by employing systematic review and quantitative content analysis methods to place gaps in the cognition base of operations.

Methods

Using a comprehensive search strategy, we searched the PubMed, PsycIFO, and CINAHL databases to place eligible interventions aimed at preventing childhood obesity with an active family unit component published between 2008 and 2015. Characteristics of study blueprint, behavioral domains targeted, and sample demographics were extracted from eligible articles using a comprehensive codebook.

Results

More than ninety% of the 119 eligible interventions were based in the United States, Europe, or Australia. Virtually interventions targeted children two–5 years of historic period (43%) or half-dozen–10 years of historic period (35%), with few studies targeting the prenatal flow (8%) or children 14–17 years of age (7%). The habitation (28%), primary wellness care (27%), and community (33%) were the most common intervention settings. Diet (90%) and physical action (82%) were more frequently targeted in interventions than media use (55%) and sleep (20%). Only xvi% of interventions targeted all four behavioral domains. In add-on to studies in developing countries, racial minorities and non-traditional families were too underrepresented. Hispanic/Latino and families of low socioeconomic status were highly represented.

Conclusions

The limited number of interventions targeting diverse populations and obesity risk behaviors beyond diet and physical action inhibit the development of comprehensive, tailored interventions. To ensure a broad prove base, more interventions implemented in developing countries and targeting racial minorities, children at both ends of the historic period spectrum, and media and sleep behaviors would be benign. This report can help inform future decision-making around the design and funding of family-based interventions to preclude childhood obesity.

Background

Childhood obesity continues to be a pervasive global public wellness consequence as children worldwide are significantly heavier than prior generations [1]. Over the past few decades, the prevalence of obesity amid children and adolescents has risen by 47% [2]. Increases have been seen in both adult and developing countries, with recent prevalence estimates of 23 and 13%, respectively [ii]. Despite evidence of a plateau in the rates of obesity, at to the lowest degree amongst young children in developed countries, current levels are yet too high, posing short- and long-term impacts on children's concrete, psychological, social, and economic well-beingness [2,three,four,v]. Of equal, if non greater business organisation, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities appear to be widening in some countries [5,6,seven,8]. Given the extensive illness burden, treatment resistance of obesity, and lack of signs of attenuation for rates in the developing world, scientists, clinicians, and practitioners are working difficult to devise and test interventions to forbid babyhood obesity and reduce associated disparities [2, 9].

1 category of interventions to prevent babyhood obesity that has grown considerably in contempo years is family-based interventions. This was in function due to a number of key reports published in 2007, including an Constitute of Medicine (IOM) report on the recent progress of childhood obesity prevention [10] and a report from a committee of experts representing 15 professional person organizations appointed to make testify-based recommendations for the prevention, assessment, and treatment of babyhood obesity [11, 12]. In both reports, parents are described as integral targets in interventions, given their highly influential role in supporting and managing the 4 behaviors that affect children's free energy balance (diet, physical activity, media use, and slumber) [13,14,15]. This includes non simply parenting practices and rules, just besides the environments to which children are exposed, and the adoption of parents' own behavioral habits by children [xv,sixteen,17,18,19].

Since the release of these reports, in that location has been a proliferation of family-based interventions to prevent and treat babyhood obesity every bit documented in at least five published reviews of this literature in the past decade [20,21,22,23,24]. While these reviews convey extensive information around intervention effectiveness, they cannot reveal gaps in the knowledge base of operations. Quantitative content analysis [25,26,27] can exist used to code intervention and participant characteristics, and a review of the resulting data can reveal areas and populations receiving a smashing bargain of attention, as well as those where few or no studies exist, thereby highlighting knowledge gaps. With a focus on babyhood obesity interventions, pertinent questions to address include: whether interventions have continued to focus primarily on diet and concrete activity, neglecting the more recently established predictors of media use and sleep [28,29,30]; whether some behaviors are more likely to be targeted among certain age groups or settings than others; and whether there are gaps with regard to the populations targeted by interventions to date, in particular, the representation of vulnerable populations (e.g. families living in developing countries, those of depression socioeconomic status, racial and indigenous minorities, immigrants, and non-traditional families) [ii, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. In improver to ethical reasons, from a pragmatic viewpoint, it is difficult to identify best practices to foreclose childhood obesity in vulnerable populations when few interventions have focused on that population [38, 39].

The goal of this study is to profile family-based interventions to prevent childhood obesity published since 2008 to identify gaps in intervention design and methodology. In particular, nosotros use quantitative content assay to systematically document intervention and sample characteristics with the goal of directing future research to address the identified knowledge gaps.

Methods

Nosotros used a multistage process informed past the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to identify family-based childhood obesity prevention interventions that were written in English and published between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2015 [40]. Using an a priori defined protocol, we identified relevant articles and systematically screened manufactures against inclusion and exclusion criteria. The systematic review protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42016042009).

Post-obit the identification of eligible studies, we conducted a quantitative content analysis to contour recent interventions for childhood obesity prevention. Content analysis, originally used in communication sciences but increasingly utilized in public health, is a research method used to generate objective, systematic, and quantitative descriptions of a topic of interest [25,26,27]. Our inquiry team has previously employed this technique to survey observational studies on parenting and childhood obesity published betwixt 2009 and 2015 [41, 42].

Search strategy and initial screening

With the help of a research librarian, two authors (TA, AA) searched three databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL) using individually tailored search strategies about appropriate for each database. The selected databases are the three most common databases used in contempo systematic reviews. Our search strategy consisted of search strings composed of terms targeting 4 concepts: (1) family (east.g. family unit, female parent, father, home), (2) intervention (east.thou. prevention, promotion), (3) children (eastward.one thousand. kid, infant, youth), and (4) obesity (eastward.thousand. overweight, torso mass) (see Boosted file 1 for full search strategy for ane database). We searched title, abstract, and medical subject headings (MeSH) or descriptor subjects (DE) term fields. Animate being studies (e.g. rats), non-original research manufactures (e.thousand. commentaries, editorials, case reports), studies written in languages other than English and studies focused on populations older than 18 years were excluded using search limits and NOT terms. We restricted the search to articles published since January ane, 2008, to capture interventions implemented subsequently the release of the IOM and proficient commission reports. Furthermore, a start point of January 2008 ensured the feasibility of this study given the labor and fourth dimension intensive process to screen and lawmaking studies. In a recent systematic review of family-based interventions for the handling and prevention of childhood obesity, more than than lxxx% of eligible studies were published since 2008 [43]. Thus, a showtime appointment of 2008 appropriately balances feasibility of implementation and the validity of the resulting data. The search end engagement was Dec 31, 2015.

The search yielded 12,274 hits, representing 9152 unique articles after removing duplicates (run into Fig. 1). Following a review of titles by iii authors (TA, AA, TY) and one research banana, 7451 articles were removed based on exclusion criteria, resulting in 1701 articles that proceeded to abstruse review. Articles were removed during title review if they were not written in English language or published in the designated time frame, were not original research articles, did not include homo subjects, did not target children, were observational studies, were not relevant to the topic of childhood obesity (east.grand. papers nigh Anorexia Nervosa), or included special clinical populations.

PRISMA flow diagram for identifying and screening eligible family-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions

Application of eligibility criteria

Three authors (TA, AA, TY) and one research assistant screened manufactures against the eligibility criteria during abstruse review, while 2 authors (TA, AA) screened during full-text review, applying the aforementioned exclusion criteria. Eligible studies included family-based interventions for childhood obesity prevention published since 2008. We defined family-based interventions as those involving active and repeated involvement in intervention activities from at least one parent or guardian [19]. Examples of intervention activities that qualify equally active parent involvement include workshops and counseling. Examples of passive interest, which were excluded, include sending abode brochures for parents, or just inviting parents to a single event, but not involving them in the intervention in an integral mode. We divers obesity interventions as those that reported at least one weight-related event (weight, torso mass index, etc.) or which cocky-identified every bit an obesity intervention. We defined interventions equally preventive if they did not explicitly focus on weight loss or direction, or if they did not recruit only children with obesity. The final inclusion benchmark was that the intervention was designed with the intent of benefiting children (child being defined every bit <18 years of age), excluded interventions in which the objective was to meliorate parent health outcomes.

Of the 1701 articles screened at the abstract level, 329 proceeded to full-text screening, of which 159 manufactures met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final pool of eligible papers (run into Additional file 2 for a list of eligible articles). We examined intervention name, trial number, the terminal name of the first author, and the last proper noun of the last author to identify manufactures that originated from the aforementioned intervention. After collating, 119 unique interventions were identified, which included interventions with published outcome data, and interventions for which only a protocol was published. Percent agreement for all screening criteria ranged between 86 and 98%. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

To ensure a fully inclusive search strategy, we also reviewed the references of a random subset of the articles coming together the inclusion criteria. A subset of 5% was chosen given the large sample size. No additional studies meeting the eligibility criteria were identified in the procedure, suggesting that the employed search was exhaustive.

Data extraction

For all eligible manufactures, we used conventional content analysis methodology [25,26,27] to extract and analyze commodity, intervention, and participant characteristics. Nosotros developed a comprehensive codebook to standardize the coding process. Multiple authors (TA, AA, AA-T) tested the codebook by coding five articles not included in the final pool of studies. An additional round of testing included 10 randomly selected articles from the report puddle. After airplane pilot testing the codebook and establishing reliability (encounter intercoder reliability), two trained coders (TA, AA) each coded one-half of the 159 eligible articles.

Article characteristics

We coded publication year, periodical, funding sources, and blazon of paper. All specific funding sources for a given intervention were extracted and classified afterward spider web-based searching. Funding sources were categorized every bit federal, foundation, corporate, or university, and then farther coded based on the specific federal, foundation or corporate agency. For type of paper, manufactures were coded as an intervention protocol or event evaluation. Articles that reported any intervention outcomes were coded as consequence evaluations; interventions that simply described the intervention (or provided only baseline data) were coded every bit protocols. Considering a seemingly large number of protocols were discovered amidst the final pool of manufactures, we elected to include them in the study. Interventions in which only a protocol has been published tend to stand for the next generation of intervention studies and thus lend to a better understanding of the field's trajectory.

Intervention characteristics

We coded a wide range of intervention characteristics including geographic region of the study, age of target child, intervention setting, length of intervention, delivery mode, evaluation pattern, intervention recipient, behavioral domains targeted, and theory used. Age of the target child at baseline was coded as prenatal (i.due east., the intervention started before nascency), 0–1 years, 2–5 years, 6–x years, eleven–13 years, and 14–17 years. If the historic period range vicious predominantly into one category, any subsequent categories were only coded affirmative if the ages of participants crossed at least two years into a given range. Intervention setting was coded equally home, primary intendance or health clinic, community-based, schoolhouse, and childcare/preschool. Community-based interventions included those taking place in community gardens, parks, or recreational facilities. Interventions taking identify at universities were also coded as community-based. In cases where intervention setting was ambiguous, or the intervention was not setting specific, nosotros coded the intervention setting as unclear.

Intervention length was coded as less than thirteen weeks (3 months), 13–51 weeks (three–11.9 months), or 52 weeks (12 months) or more. Two different types of intervention delivery modes were coded: in-person and engineering-based. Technology-based approaches included those using computers, social media, text messages, or anything else involving the Internet. Evaluation design was coded as either randomized-controlled trial or quasi-experimental trial. Nosotros also extracted information on intervention recipients (i.e. those who directly received the intervention plan or materials). This was coded as adults, children, or both. Behavioral domains targeted included nutrition, concrete activity, media use, and sleep. Finally, we coded use of theory. Theories were specified using the following categories: social cognitive theory, parenting styles, ecological frameworks, transtheoretical model of behavior change, health conventionalities model, theory of planned behavior, or other. For historic period category, intervention setting, delivery fashion, intervention recipients, and theory, multiple categories could be selected.

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics were coded for the inclusion of participants from underserved populations and non-traditional families, and racial/ethnic composition of the sample. We coded sample characteristics for outcome evaluations only (n = 84 studies) because intervention protocols generally practice not include this information. We coded whether the intervention included any participants from the following underserved or non-traditional groups: depression socioeconomic condition (SES), racial/indigenous minorities (i.e., Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Indigenous), immigrant families, single parents, non-biological parents, and non-residential parents. Low SES was defined as either low income (cocky-identified by the study) or low education (loftier school diploma or less). Families participating in low-income qualifying programs (Women, Infants, and Children services, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Plan, free or reduced school dejeuner, Head Start, etc.) were considered low SES. We coded parents as unmarried if they self-identified as such, were not cohabitating, or were widowed or divorced. In studies where express information was provided and marital status was simply dichotomized equally married or not married, not married was used equally a proxy for single. Finally, we coded whether the sample included participants from each racial/ethnic grouping (i.east. White, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Indigenous, and multiracial/other). For all sample characteristics, in add-on to coding whether families belonging to each of the groups were included, we also coded whether they made up at least fifty% of the sample, as well every bit 90% of the sample. The purpose of these categories was to distinguish between studies that included but a few families from a given category and those in which at least half the sample belonged to the category. If at least xc% of the families included in a sample belonged to a given category, the sample was considered to be predominantly that category (e.k. predominantly-Hispanic). Samples coded affirmative for 90% criteria were also coded affirmative for the 50% criteria.

Inter-rater reliability

Both coders coded randomly selected articles from the final study pool until reliability was sufficiently established. Ultimately, this included four rounds of coding a full of 55 articles. We computed Cohen's kappa every bit a mensurate of agreement betwixt the coders, using weighted kappas for ordinal variables [44]. The final average kappa across all variables was 0.87, and the average percent understanding was 92%. Three variables had kappas below 0.70, the conservative threshold for adequate inter-rater reliability [45]. These variables included the post-obit: inclusion of children 11–13 years quondam (kappa 0.36), inclusion of children 14–17 years old (kappa 0.65), and childcare/preschool setting (kappa 0.46). Because percent agreement for each of these variables was loftier (>89%), and given that kappa coefficients are difficult to translate when variability is low [45, 46], which would issue from a category (e.k. inclusion of children 14–17 years) being infrequently coded or endorsed, they were retained in the analyses. Coders were retrained on the three variables prior to coding the remainder of the articles.

Data synthesis and analysis

Both inter-rater reliability and all other analyses were conducted in STATA 13 [StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA]. One coder (TA) cleaned the data. The majority of missing data was not reported (i.e., were missing by blueprint) and therefore coded every bit '0' (no/non sure). Where data were missing, ane of the coders (TA) returned to the total-text article to ostend and correct any errors.

For article characteristics (e.g. publication yr, journal), the unit of measurement of analysis is article, with a denominator of 159 articles. For intervention and sample characteristics, which are presented in Tables 1-iii, the unit of analysis is intervention. In instances where multiple studies were published on the same intervention, the data extracted from each study were synthesized into a single entry [47]. For example, if both a protocol and outcome evaluation were published for an intervention, the intervention was marked equally having an upshot evaluation. As a effect, a denominator of 119 interventions was used to assess intervention characteristics. Interventions with a protocol only were non included in the assessment of sample characteristics considering sample data is infrequently reported in such papers. Thus the denominator for sample characteristics was 85 interventions with published outcome data.

We also examined article and intervention characteristics separately for protocols and event evaluations. Given that few differences were identified, this information is presented in Additional file three: Table S1 to streamline the presentation of results.

Results

The number of eligible manufactures published each year was every bit follows: 2008 = 6 (four%), 2009 = 5 (iii%), 2010 = 14 (ix%), 2011 = fifteen (nine%), 2012 = 33 (21%), 2013 = 35 (22%), 2014 = 23 (14%), and 2015 = 28 (eighteen%). The predominant journals in which articles were published included BioMed Central Public Health (n = 28, xviii%), Contemporary Clinical Trials (n = 12, 8%), Babyhood Obesity (n = 9, 6%), Pediatrics (north = 7, 4%), Pediatric Obesity (northward = half-dozen, 4%), and Preventive Medicine (n = half dozen, 4%).

Intervention characteristics

Eligible articles described 119 unique interventions. Table 1 summarizes boosted intervention characteristics for eligible interventions. For more a fourth of these interventions (due north = 34, 29%), only an intervention protocol was identified (i.e., no published outcomes were bachelor). More half (n = 66, 56%) of the interventions were based in the U.South. Studies based in Europe/United Kingdom (due north = 30, 25%), Commonwealth of australia/New Zealand (n = 10, 8%), and Canada (n = six, 5%) comprised 38%. Few interventions were conducted in countries in Key America, South America, Asia, Africa, the Middle Eastward, or the Caribbean.

Less than a third of interventions were implemented for a yr or more (northward = 33, 28%). Interventions that were implemented in-person (n = 101, 85%) were more than common than those delivered using technology (n = 27, 23%). Fourteen (12%) of interventions had both in-person and technology components. Five interventions (four%) had neither an in-person nor a technology component; these interventions consisted of printed materials and phone calls. Nearly three out of 4 interventions utilized a randomized controlled trial pattern (n = 87, 73%). Considering active parent date was a requirement for eligibility in this review, parents were intervention recipients in all interventions. Children were likewise intervention recipients in approximately half of the interventions (n = 65, 55%).

A slight majority of interventions were federally funded (north = 75, 63%). Of these, about half (north = 34, 29% of the 119 eligible interventions) received funding from the National Institutes of Health, with the National Found of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (north = xiv, 12%) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (n = 7, half-dozen%) beingness the two leading funding institutes (information not shown). The United States Department of Agriculture funded 10 (8%) interventions. Xx-3 (nineteen%) interventions received federal funding from countries other than the United States, with Commonwealth of australia funding the most (north = 6, five%). Of the 50 (42%) interventions funded by foundations, the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation was the leading funder (north = 5, four%). A like proportion of interventions received corporate (n = 21, 18%) or university funding (due north = 23, 19%). Many interventions (n = 46, 39%) received multiple types of funding, and funding source was not listed in 8 (7%) of interventions.

A majority of interventions mentioned theory (northward = 85, 71%), with many (due north = 34, 29%) using multiple theories. However, interventions varied profoundly with respect to how heavily theory was emphasized. Social cognitive theory was the most widely noted theory (n = 49, 41%).

Approximately forty% of interventions targeted families with children ages two–5 years (n = 51, 43%) or six–10 years (n = 42, 35%), whereas fewer than 10% of interventions targeted families during the prenatal flow (n = x, 8%) or families of children with 14–17-year-olds (northward = eight, 7%). One in iii interventions were implemented in a home setting (n = 33, 28%), a master care/health clinic (north = 32, 27%) or in the customs (n = 39, 33%), and ane in v (due north = 24) were implemented in multiple settings. Finally, only over half (northward = 69, 58%) of studies targeted a behavioral domain beyond diet and physical activeness (i.e., they targeted media employ and/or slumber in addition to diet and physical action), and simply a few (n = 3, three%) interventions did non target either diet or physical activity.

Table 2 provides a cross tabulation of age of target child, setting, and behavioral domains. A number of patterns are apparent. First, interventions that targeted children in the before years of life (prenatal to age 5 years) tended to be focused in the home (n = 28, 31%) and primary care settings (northward = 30, 33%), whereas interventions that targeted older children occurred nearly frequently in community (due north = 40, 53%) and school (n = 20, 27%) settings. Second, media use was least frequently included in school-based interventions (n = 9, 43%). Physical activity was most oftentimes targeted in a schoolhouse setting (northward = 21, 100%), and least likely to be targeted in homes (n = 23, 70%). Slumber was nearly often included in dwelling house-based (due north = 8, 24%), health-based (n = 8, 25%), and childcare-based (north = 3, 27%) interventions; it was seldom targeted in families with school-age children (n = 4, ten%) and has not been targeted in families with children older than ten years of age.

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics are summarized in Tabular array 3. Underserved families appeared well-represented, specially low SES families (n = 62, 73%). A slight majority of samples included at least some racial or ethnic minority families (n = 46, 54%), and but over a quarter included immigrant families (northward = 24, 28%). Ethnic minorities (i.e., Hispanics) were amend represented than racial minorities. About half of the interventions included families identifying every bit Hispanic/Latino (n = 40, 47%).

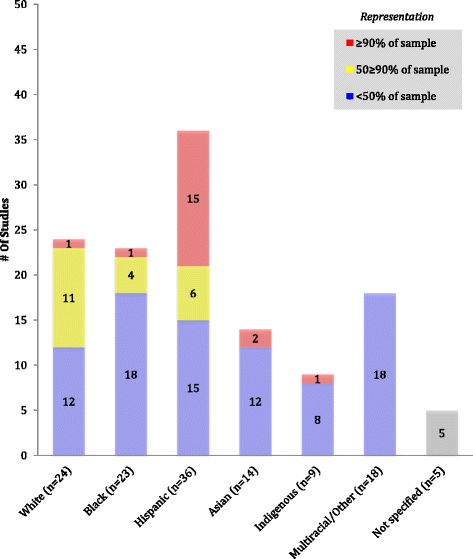

The most frequently represented racial group was White (n = 30, 35%), followed by Black/African American (due north = 26, 31%), Asian (n = 20, 24%), and and then Indigenous (n = 12, xiv%). Notably, many interventions (n = 29, 34%) did not specify the racial/ethnic background of families. Fig. two provides a more detailed assessment of the racial/ethnic composition of U.S.-based interventions (non-U.Southward. interventions infrequently reported participant race or ethnicity and were therefore not included). In 42% (northward = 21) of U.South.-based interventions, Hispanic/Latino families fabricated up at least half of the sample, and in xxx% (n = 15) of interventions they made up at least 90% of the sample. Once again, families identifying as White were the almost represented racial group (n = 24, 48%). Less than 20% of studies included a sample that was at least half Black/African American (n = v, 10%), Asian (northward = 2, iv%), or Indigenous (n = ane, 2%).

Inclusion and representation for racial/ethnic groups in U.Southward. family-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions (n = fifty)

Few studies included non-traditional families; less than a third of interventions included any single parent households (northward = 23, 27%) and less than five% included non-biological parents (n = 2, 2%) or non-residential parents (n = 0, 0%).

Comparing protocols to outcome evaluations

When comparing interventions with evaluations to those with protocols only, a proxy for more recent interventions, interventions with protocols targeted more domains than those with evaluations. The proportion of evaluation and protocols that targeted just i behavioral domain was 20 and 12%, respectively, while the proportion targeting all four behavioral domains was 13 and 24%, respectively. Other notable differences were that interventions with protocols only were more than likely to be of longer duration, utilize engineering science, prefer a randomized controlled trial design, target parents exclusively, receive federal funding, and use theory (meet Boosted file 3: Table S1).

Word

Parents are important agents of change in the babyhood obesity epidemic [20, 22, 48, 49]. This study used rigorous systematic methods to deport a quantitative content assay of family-based interventions to forbid childhood published between 2008 and 2015 to profile the field of recent family-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions and place knowledge gaps. We identified gaps in both intervention content and sample demographics. Key research gaps include studies in low-income countries, interventions for children on both the lower and college ends of the age spectrum, and interventions targeting media use and sleep. Racial minorities and children from non-traditional families have also been underrepresented.

Intervention gaps and implications

The vast majority of studies were conducted in adult, or high-income, countries. Given the rapid increase of obesity as a significant public health burden in developing countries, this study demonstrates a need for further intervention efforts in low- and middle-income countries [50, 51]. Although obesity rates are lower in low- and middle-income countries than developed countries, two-thirds of people with obesity worldwide live in developing countries where rates of obesity are increasing [ii]. The small number of studies in these geographic regions limits the development of locally relevant programs and policies aiming to address the growing trouble of obesity in these regions.

Non-traditional families were underrepresented in interventions. This is concerning given that children from not-traditional families accept an elevated risk for obesity [31,32,33,34,35,36]. The changing nature of family structures, including the increasing number of single-parent households over time, [52] calls for a more than inclusive approach to defining what is considered a family in research. Like non-traditional families, Black/African American, Asian, and Ethnic families have been underrepresented. Racial and indigenous minorities are vulnerable populations who experience elevated risk for obesity [33, 34]. Initiatives to fund interventions specifically targeted at racial and ethnic minorities may have increased the number of interventions targeting Hispanics, but non racial minorities. Thus, more than efforts are needed that specifically target families identifying as races other than White. The lack of studies including acceptable representation of these groups limits the scientific community's agreement of effective strategies in loftier-risk communities and fails to fully accost noted health disparities.

Family-based childhood obesity prevention interventions have focused heavily on children 2–10 years of historic period, despite the robust evidence demonstrating the importance of prevention efforts equally early as infancy and the prenatal period [53, 54]. Establishing good for you habits early in life is disquisitional given the difficulty of changing energy-residue behaviors afterwards on. While it has been established that prenatal life influences childhood obesity gamble, the depression number of interventions first in the prenatal period, in item, may be due to a full general lack of agreement of the mechanisms responsible for this association, and general debate in the field about how early intervention efforts should begin [55, 56].

This report also revealed gaps in behavioral domains targeted, as interventions have not fairly targeted media use and slumber. Moreover, simply 16% of interventions targeted all four behavioral domains. The emphasis of interventions on diet and physical activity may reflect their relative contribution to obesity risk. However, behavioral risk factors for obesity are interconnected, and thus may be ameliorate addressed by considering complimentary and supplementary behaviors [57,58,59]. While it can be argued that targeted messages may have a greater affect, the research gaps identified in this study (e.g. the lack of interventions targeting slumber among older children) highlight areas of needed research in the field. It is worth acknowledging how varied intervention length was across studies, with about a third of interventions existence less than iii months long. This is important given the difficulty in making and sustaining lifestyle changes.

Comparisons with observational studies

The results of this study are consistent with findings from a content analysis by Gicevic et al. on observational research on parenting and childhood obesity published over a similar time frame [41]. The majority of studies were conducted in adult countries; diet and concrete action were the most heavily targeted behavioral domains; most studies targeted children ages 2–x; and at that place was a low representation, or at least specification, of non-traditional families. Also consistent with Gicevic et al., non-U.S. studies seldom reported the racial/ethnic composition of the sample [41].

Limitations

At that place are several limitations to this study that are worth noting. Outset, this study focused on manufactures published over a relatively narrow time-period. Given the immense number of records initially identified, we needed to consider the feasibility of screening and then thoroughly coding eligible articles. Thus nosotros decided to focus on recent literature. Additionally, it was not a focus of this report to look at time trends. Time to come studies that wish to meet how the field is irresolute should exercise fourth dimension-trend analyses, ideally taking into account a longer period of time. Another limitation of this written report is that nosotros did not appraise intervention effectiveness or quality. While this may limit the potential utility of this review, we chose to focus on the results of the content analysis and not include this data because it is included in prior reviews of family unit-based interventions for childhood obesity prevention published in the past ten years [20,21,22,23,24, threescore]. Although systematic reviews can place effective intervention strategies, they cannot identify the absence of information or gaps in the literature. This study explicitly addressed this shortfall in prior reviews. Lastly, the results of this written report may exist influenced by the number and choice of databases searched, and may exist field of study to publication bias. Given the big book of studies (~7000) obtained by searching PubMed, and the considerable overlap with other databases (i.eastward. the number of duplicates), we limited our search to the three most commonly searched databases in previous reviews [twenty,21,22,23,24, 41, sixty]. Past limiting our search, it is possible that a few otherwise eligible studies were missed. It is as well possible that including other databases (due east.one thousand. EMBASE, Dissertation Abstracts International) would have slightly increased the proportion of non-U.South. based interventions.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, this written report used a novel approach to synthesize and profile the contempo literature on family-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions. Results demonstrate the current emphasis in interventions, and lack of adequate representation of various groups. More than interventions that recruit diverse populations, and target behaviors beyond diet and concrete activity, are needed to improve understand the influence of these characteristics when designing and implementing family unit-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions. The results of this report can be used to inform decision-making around intervention pattern and funding aimed at filling gaps in the knowledge base. Filling these gaps volition lead to a better understanding of how best to target a broad range of behaviors in diverse populations.

Abbreviations

- IOM:

-

Plant of Medicine

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic condition

- U.South:

-

Usa

References

-

Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, Hall KD, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, et al. Child and adolescent obesity: function of a bigger picture. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2510–20.

-

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson One thousand, Thomas B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–81.

-

Halfon N, Larson Thousand, Slusser W. Associations between obesity and comorbid mental health, developmental, and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample of The states children aged x to 17. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(i):six–13.

-

Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, Hacking B, Alexander D, Stewart L, Kelnar CJ. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(9):748–52.

-

Olds T, Maher C, Zumin S, Peneau S, Lioret Southward, Castetbon K, et al. Testify that the prevalence of babyhood overweight is plateauing: information from nine countries. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(5–6):342–60.

-

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the U.s., 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–fourteen.

-

Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity amongst United states children and adolescents, 1976-2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(1):12–20.

-

Stamatakis E, Wardle J, Cole TJ. Childhood obesity and overweight prevalence trends in England: evidence for growing socioeconomic disparities. Int J Obes. 2009;34:41–7.

-

Battle EK, Brownell KD. Confronting a rising tide of eating disorders and obesity: handling vs. prevention and policy. Addict Behav. 1996;21(6):755–65.

-

Koplan JP, Liverman CT, Kraak 6, Wisham SL. Progress in preventing childhood obesity: how do we measure up? Washington: National Academy Printing, Plant of Medicine; 2007.

-

Barlow SE. Adept committee. Good committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and boyish overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–92.

-

Davis MM, Gance-Cleveland B, Hassink S, Johnson R, Paradis G, Resnicow Grand. Recommendations for prevention of childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2007 December;120(Suppl iv):S229–53.

-

Birch LL, Davison KK. Family unit environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2001;48(iv):893–907.

-

Jago R, Edwards MJ, Urbanski CR, Sebire SJ. General and specific approaches to media parenting: a systematic review of current measures, associations with screen-viewing, and measurement implications. Child Obes. 2013;ix(Suppl):S51–72.

-

Loprinzi PD, Trost SG. Parental influences on concrete activity beliefs in preschool children. Prev Med. 2010;50(3):129–33.

-

Pearson Due north, Biddle SJ, Gorely T. Family unit correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(2):267–83.

-

Jago R, Sebire S, Lucas PJ, Turner KM, Bentley GF, Goodred JK, Steqart-Brownish South, Fox KR. Parental modeling, media equipment and screen-viewing among young children: cross-sectional report. BMJ Open up. 2013;3(four). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002593.

-

Nepper MJ, Chai W. Associations of the domicile food surround with eating behaviors and weight status amid children and adolescents. J Nutr Nutrient Sci. 2015;S12(004). doi:10.4172/2155-9600.S12-004.

-

Janz KF, Dawson JD, Mahoney LT. Tracking concrete fitness and concrete activity from childhood to adolescence: the muscatine study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(7):1250–seven.

-

Hingle Medico, O'Connor TM, Dave JM, Baranowski T. Parental interest in interventions to improve kid dietary intake: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2010;51(2):103–11.

-

Kitzmann KM, Beech BM. Family unit-based interventions for pediatric obesity: methodological and conceptual challenges from family unit psychology. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20(2):175–89.

-

Golan Grand. Parents as agents of alter in childhood obesity—from research to practice. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(ii):66–76.

-

Knowlden AP, Sharma K. Systematic review of family and dwelling house-based interventions targeting paediatric overweight and obesity. Obes Rev. 2012;13(six):499–508.

-

Sung-Chan P, Sung YW, Zhao Ten, Brownson RC. Family-based models for childhood-obesity intervention: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2013;14(4):265–78.

-

Berelson B. Content assay in advice research. New York: Free Press Content analysis in communication inquiry; 1952. p. 220.

-

Manganello J, Blake N. A study of quantitative content analysis of wellness letters in U.S. Media from 1985 to 2005. Health Commun. 2010;25(v):387–96.

-

Krippendorff K. Content assay: an introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1980.

-

Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson Thousand, Colditz GA, Dietz WH. Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the Us, 1986-1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:356–62.

-

Chen Ten, Beydoun MA, Wang Y. Is slumber elapsing associated with childhood obesity? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obesity. 2008;16(two):265–74.

-

Li L, Zhang S, Huang Y, Chen Chiliad. Slumber duration and obesity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(4):378–85.

-

Chen AY, Escarce JJ. Family unit structure and babyhood obesity, early childhood longitudinal study—kindergarten cohort. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A50.

-

Gibson LY, Byrne SM, Davis EA, Blair Due east, Jacoby P, Zubrick SR. The role of family and maternal factors in childhood obesity. Med J Aust. 2007;186(xi):591–v.

-

Egeland GM, Harrison GG. Wellness disparities: promoting ethnic peoples' health through traditional food systems and cocky-conclusion. In: indigenous peoples' food systems & well-being. Rome: FAO; 2013.

-

Felgal KM, Carroll Doctor, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass alphabetize among US adults 1999-2010. JAMA. 2014;307(5):491–7.

-

Health, United States. 2002 with Chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville: National Centre for Health Statistics; 2002.

-

Kington RS, Nickens HW. Racial and ethnic differences in health: contempo trends, current patterns, future directions. In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, editors. America becoming: racial trends and their consequences. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001.

-

Kaushal N. Adversities of acculturation? Prevalence of obesity among immigrants. Health Econ. 2009;xviii(iii):291–303.

-

Dumbka L, Garza C, Roosa M, Stoerzinger H. Recruitment and retention of high-risk families into a preventative parent training intervention. J Primary Prevention. 1997;18(1):25–39.

-

Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority enquiry participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:1–28.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;2009, half dozen(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

-

Gicevic S, Aftosmes-Tobio A, Manganello JA, Ganter C, Simon CL, Newlan Due south, Davison KK. Parenting and childhood obesity research: a quantitative content analysis of published enquiry 2009-2015. Obes Rev. 2016;17(8):724–34.

-

Davison KK, Gicevic South, Aftosmes-Tobio A, Ganter C, Simon CL, Newlan S, Manganello JA. Fathers'representation in observational studies on parenting and babyhood obesity: a systematic review and content analysis. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(xi):1980.

-

Morgan PJ, Young Physician, Lloyd AB, Wang ML, Eather Northward, Miller A, et al. Involvement of fathers in pediatric obesity treatment and prevention trials: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162635.

-

Hallgren KA. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2012;viii(1):23–34.

-

Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):423–9.

-

Lantz CA, Nebenzahl E. Beliefs and estimation of the kappa statistic: resolution of the two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(iv):431–four.

-

Higgins J, Greenish S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2011. Version v.1.0. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed viii November 2016.

-

Jelalian Eastward, Saelens BE. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: pediatric obesity. J Pediatric Psychol. 1999;24(3):223–48.

-

Campbell Thousand, Hesketh K. Strategies which aim to positively touch on weight, physical activeness, diet and sedentary behaviours in children from zero to five years. A systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2007;viii:327–38.

-

Popkin BM. The diet transition and obesity in the developing world. J Nutr. 2001;131(3):871S–3S.

-

Prentice AM. The emerging epidemic of obesity in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(1):93–9.

-

McLanahan S, Percheski C. Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:257–76.

-

Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P, Kleijnen. Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later on obesity. BMJ. 2005;331(7522):929.

-

Monteiro PO, Victora CG. Rapid growth in infancy and childhood and obesity in later life—a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2005;half dozen(2):143–54.

-

Oken Due east. Maternal and kid obesity: the causal link. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2009;36(two):361–77.

-

Whitaker RC, Dietz WH. Role of the prenatal environment in the development of obesity. J Pediatr. 1998;132(5):768–76.

-

Prochaska JJ, Leap B, Nigg CR. Multiple health behavior modify research: an introduction and overview. Prev Med. 2009;46(three):181–eight.

-

Driskell Thou-M, Dyment Southward, Mauriello L, Castle P, Sherman K. Relationships amongst multiple behaviors for childhood and adolescent obesity prevention. Prev Med. 2008;46(30):209–15.

-

Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity in children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(five):963–75.

-

Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: the skinny on interventions that work. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(5):667–91.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Carol Mita and Selma Gicevic for their assistance in constructing the search strategy. We would also like to acknowledge Martina Sepulveda for assisting with screening.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study and have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Availability of data and materials

The data extracted in the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable asking.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

TA and AA developed the search strategy, performed the literature search, conducted article screening, and data extraction, and drafted the manuscript. In addition, TA cleaned the data, ran the analyses, and generated the Tables. TY assisted with commodity screening and drafted a portion of the manuscript. AAT created the codebook, assisted with screening and coding training, provided input on issue interpretation, and edited the manuscript. KKD conceptualized the study, supervised the systematic review process, provided input on coding categories, helped generate the tables, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the terminal manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Full search strategy for PubMed database to identify eligible family-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions published between 2008 and 2015. (DOCX 135 kb)

Boosted file 2:

List of eligible articles published between 2008 and 2015 detailing a family-based childhood obesity prevention intervention. (DOCX 210 kb)

Boosted file 3: Table S1.

Intervention characteristics of family-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions separating studies with evaluations from protocols. (DOCX 116 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/naught/one.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Ash, T., Agaronov, A., Young, T. et al. Family-based babyhood obesity prevention interventions: a systematic review and quantitative content analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Human action 14, 113 (2017). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12966-017-0571-2

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0571-2

Keywords

- Childhood obesity

- Diet

- Physical activity

- Media apply

- Sedentary beliefs

- Sleep

- Family-based

Source: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-017-0571-2

0 Response to "Parentã¢â‚¬â€œchild Interactions and Obesity Prevention a Systematic Review of the Literature"

Post a Comment